By Elizabeth Granger

She’s energetic. She’s now. She’s it.

She’s Julian Opie’s Ann Dancing, the perpetually swaying digital woman who captures the essence of Mass Ave’s exuberance.

Mindy Taylor Ross of Indianapolis, art curator and owner of Art Strategies, helped bring Ann to Indianapolis in 2007. “She engages people,” Ross says. “I see people sashaying like her.”

Ross says Ann is her favorite piece of public art.

Ah, yes … public art. A term with different meanings for different people. Ross prefers to call it art in public spaces. Often outdoors but not always, and free to the general public.

Ironically, it’s not always on public land. Consider the multitude of murals in the state – of Vonnegut in Indianapolis, jazz musicians in Richmond, local history in Ligonier. Many on privately-owned buildings but visible to a lot of people.

Artist Pamela Bliss began her mural career in Richmond in 1997 to commemorate the city’s jazz heritage. In 2010 she invited other artists to join her. Today there are more than 70 murals in Wayne County, created by more than 15 artists.

Fort Wayne is experiencing mural-mania this summer with local artists brightening up downtown alleys through the Art This Way program. Bill Brown, president of Downtown Fort Wayne, says, “Public art enhances public grounds in a way that goes beyond brick and mortar. Public art gives the public realm a soul.”

In 2014 Fort Wayne’s sculpture scene exploded with not one or two but 50 different pieces, each one a bike rack. Sculpture with Purpose “ties our love of outdoor recreation to our insistence on the priority of public art,” says Kristen Guthrie of Visit Fort Wayne. “Each one is different, so people enjoy searching out new ones, but the fact that they are all functional bike racks is just so smart.”

They’re a different take on sculpture, long a staple in public art. Important events and important personas live forever in stone, marble, bronze, clay, plastics. Indianapolis is considered to have more monuments and memorials dedicated to veterans than any other city except Washington, D.C. Among them are the Soldiers and Sailors Monument, Indiana War Memorial, USS Indianapolis Memorial, and Congressional Medal of Honor Memorial.

Statues immortalize individuals and events that are serious – and not so serious.

Who wouldn’t be charmed by children playing crack the whip in Columbus, frolicking in front of the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis or cooling off in Depew Fountain in University Square in Indianapolis?

Grant County offers the Garfield Trail with a dozen bright orange fiberglass Garfield the cat statues, each about 5 feet tall and each dressed differently. Jim Davis, Garfield’s creator, hails from Grant County.

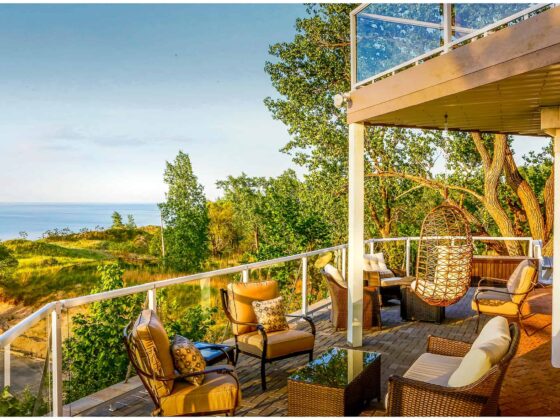

Living art plays a part, too, growing and changing with the seasons. Consider gardens both public and private, each fashioned by a horticultural artist.

Elkhart County’s quilt gardens bloom throughout the summer. Walking paths have been incorporated into the patterns so people can walk right into the gardens, often lending an artistic hand when they pull weeds or deadhead blooms.

“What we love most about public art, whether it’s gardens, sculptures, water features or something else, is that it brings people together,” says Terry Mark of the Elkhart County Convention and Visitors Bureau. “They are an invitation for people to linger and to converse and build relationships with each other and with the community surrounding it.”

Brigette Cook Jones of Hancock County Tourism agrees and adds, “You can interact with it, more so today because we have smartphones.” She said the top three tourism-related photos are of food, signs, and statues – with people in the photos. It makes her definition of public art broad and includes signs, banners, even manhole covers.

Jones likes when children get involved, as they did in helping to pay for a James Whitcomb Riley statue 100 years ago and recently for a Riley bench in front of his home in Greenfield.

Those sit-by-me benches inspire interaction. Within moments a photo can be taken and posted on social media. In addition to the Riley bench are those with Gov. Frank O’Bannon in Corydon, Desiderata poet and philosopher Max Ehrmann in Terre Haute, and automobile pioneer Elwood Haynes in Kokomo.

Visitors can sit next to astronaut Neil Armstrong in West Lafayette, or walk in his moon boot impressions. A piano with songwriter Hoagy Carmichael beckons in Bloomington. A woman at the public library in Goshen invites a child to sit with her to read.

A couple of sculptor J. Seward Johnson’s popular likenesses sit on benches in Carmel, while more offer lifelike glimpses into ordinary activities. “We like to refer to these as our walkable outdoor museum,” says Carmel mayor Jim Brainard. He adds the sculptures are popular with residents and visitors alike “who are quick to whip out their cell phones to pose for selfies and family photos to capture the moment. We also have noticed that some of our more spirited residents and visitors like to dress the statues in their favorite sports team regalia before big games; or scarves and mittens will suddenly appear on the statutes before a snowstorm. Clearly, the public is having fun with them.”

A touring Johnson exhibit spent last summer in Elkhart County. This is the fourth year for such exhibits in Crown Point, which this year also includes a 30-foot-tall Johnson statue of the kissing sailor and nurse titled Embracing Peace.

In the South Shore Welcome Center, in Hammond, visitors can be a part of record-breaking history by helping create a beautiful mural made with recycled Mardi Gras beads. “Bead Town: Along the South Shore” will highlight iconic buildings, historic places, landscapes and people along the southern shores of Lake Michigan. The mural will also feature real people from around the globe making it an international work of art. Thousands of participants will place nearly 15 million recycled beads on a 3,311 sq. ft. mural in an attempt to break a new Guinness World Record.

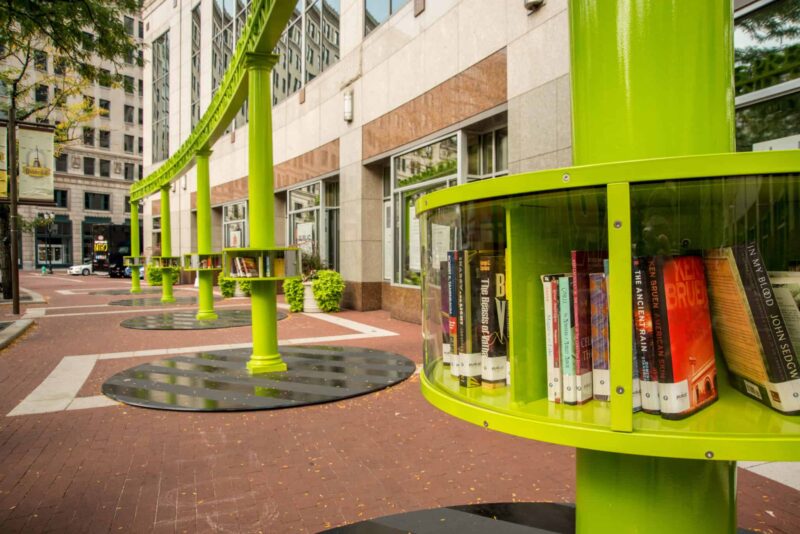

Towns around Indiana are embracing the public art movement by turning dark alleys into “Artist Alleys.” In addition to Fort Wayne, Kokomo has transformed a dim alley between the County building and the Kokomo Art Association Artworks Gallery into an industrial, outdoor art gallery that enlivens the downtown landscape.

In White River State Park in Indianapolis, it’s a tire swing that invites visitors to become part of the artwork. And a traveling “INDY” sign is missing its “I” – until someone becomes the “I.” Footprints on the sculpture show visitors where to stand. “Kindly ask someone to take your picture,” the directions read. “Post to your favorite social network with hashtag #LOVEINDY.”

A perfect chance to become public art.